Embark on a photographic journey where challenging lighting transforms into your creative ally. This guide unveils the secrets to mastering how to shoot against strong backlight, turning potential pitfalls into stunning visual triumphs.

We will delve into the fundamental principles that govern photography in bright conditions, exploring the common issues like silhouetting and underexposure, while also uncovering the artistic possibilities such as dramatic rim lighting and captivating lens flares. Understanding how to manage exposure through metering modes and essential camera settings will be key to achieving balanced and impactful images, even when faced with the most intense light sources.

Understanding the Challenge of Shooting Against Strong Backlight

Shooting directly into a strong light source, such as the sun or a bright window, presents a unique set of challenges for photographers. This scenario can easily lead to images where the intended subject is lost in darkness or rendered as a stark silhouette. However, with a proper understanding of the underlying photographic principles and the right techniques, this challenging condition can be overcome and even leveraged for creative effect.The fundamental issue with shooting into backlight lies in how cameras measure light and how they attempt to create a balanced exposure.

Cameras typically aim to expose for the brightest part of the scene, or an average, which often results in the foreground subject being significantly underexposed when the background is overwhelmingly bright. This leads to common problems that require specific strategies to mitigate.

Core Photographic Principles in Backlight Scenarios

The difficulty in shooting against strong backlight stems from the fundamental principles of exposure and dynamic range. A camera’s sensor has a limited capacity to capture detail in both the very bright and very dark areas of a scene simultaneously. When the difference between the brightest and darkest parts of a scene (the dynamic range) exceeds the camera’s capability, a compromise must be made, often at the expense of the subject.The inverse square law of light also plays a role.

Light intensity diminishes rapidly with distance. When the primary light source is behind the subject, the subject is much further from the light than the background, causing the subject to receive significantly less illumination compared to the background. This disparity is what the camera struggles to reconcile.

Common Visual Problems in Backlight

When shooting against strong backlight, several visual issues commonly arise, primarily related to underexposure and the camera’s inability to capture detail in both extreme highlights and shadows simultaneously.

- Silhouetting: This occurs when the camera prioritizes exposing for the bright background. The subject, receiving very little light, appears as a dark shape with little to no discernible detail, resembling a silhouette.

- Underexposed Subjects: Even if the subject is not a complete silhouette, it will likely appear too dark, with lost shadow detail. The camera’s automatic exposure settings are often fooled by the bright background, leading to an overall underexposed image where the subject is barely visible.

- Loss of Detail: In very high contrast situations, the camera may struggle to capture detail in either the highlights or the shadows. If it exposes for the background, the subject’s details are lost. If it attempts to expose for the subject, the background can become completely blown out, losing all texture and color information.

Potential Creative Effects of Backlight

While often seen as a challenge, shooting into backlight can also yield beautiful and dramatic creative effects that add depth and visual interest to photographs. Understanding how to control and utilize these effects can transform a potentially problematic situation into an artistic opportunity.

- Rim Lighting: This is one of the most sought-after effects of backlight. A thin, bright Artikel of light appears around the edges of the subject, separating it from the background and giving it a three-dimensional quality. This is particularly effective for portraits and subjects with distinct Artikels.

- Lens Flare: When light sources are directly in or near the frame, they can enter the lens and create streaks, circles, or polygonal shapes of light. While sometimes considered a nuisance, intentional lens flare can add a dreamy, artistic, or energetic feel to an image, reminiscent of vintage photography or cinematic styles.

- Atmospheric Haze and Glow: Backlight can create a soft, diffused glow around the subject or in the air, especially when there is dust, fog, or moisture present. This can lend a mystical, ethereal, or nostalgic mood to the photograph.

- Highlighting Textures: The strong directional light from behind can accentuate textures on surfaces, such as hair, fabric, or natural elements like leaves and water, adding a sense of depth and detail.

Importance of Metering Modes in Managing Exposure

The way a camera measures light, known as the metering mode, is crucial when dealing with strong backlight. Different metering modes analyze the scene in different ways, and selecting the appropriate one can significantly improve your exposure accuracy and prevent common backlight pitfalls.Your camera’s metering mode tells it how to interpret the light it sees to determine the correct exposure settings.

In high-contrast scenes like those with strong backlight, the default settings might not be ideal.

- Evaluative/Matrix Metering: This mode analyzes the entire scene, dividing it into zones and calculating an average exposure. While useful for general scenes, it can be easily fooled by strong backlight, often leading to underexposed subjects.

- Center-Weighted Metering: This mode gives more importance to the light in the center of the frame, with less emphasis on the edges. It’s a good compromise but can still be influenced by a very bright background if the subject is small and in the center.

- Spot Metering: This is arguably the most effective mode for controlling exposure in backlight. Spot metering measures the light from a very small area of the scene, typically around 1-5% of the frame, centered on your focus point. By taking a reading from your subject’s face or the area you want correctly exposed, you can ensure the subject is properly illuminated, even if the background becomes brighter or darker than ideal.

For critical exposure control in backlight, especially when you want to avoid silhouetting, using spot metering on your subject is highly recommended. You can then use exposure compensation to fine-tune the brightness.

Essential Camera Settings and Techniques for Backlight Situations

Shooting into a strong light source presents a unique set of challenges, but with the right camera settings and techniques, you can transform these difficult conditions into opportunities for dramatic and captivating imagery. Understanding how your camera meters light and how to override its default behavior is crucial for success. This section will guide you through the essential adjustments to ensure your subjects are well-exposed, even when the background is ablaze with light.Mastering exposure compensation is your primary tool for balancing the light in a backlit scene.

Your camera’s automatic modes often try to expose for the brightest part of the scene, which can lead to your subject being underexposed, appearing as a silhouette. By intelligently adjusting the exposure compensation, you can tell your camera to prioritize a brighter exposure, bringing out the details in your subject.

Adjusting Exposure Compensation for Balanced Images

Exposure compensation is a direct way to influence the brightness of your image beyond what the camera’s meter might suggest. It allows you to manually tell your camera to make the image brighter or darker than its default reading. When shooting against strong backlight, you will almost always need to increase the exposure.Here’s a step-by-step guide to using exposure compensation:

- Identify the Need: Observe your scene. If your subject appears too dark compared to the bright background, you need to increase exposure.

- Locate the Exposure Compensation Control: This is typically represented by a button or dial marked with a +/- symbol. Consult your camera’s manual if you are unsure of its location.

- Increase Exposure: Dial in positive values (e.g., +0.3, +0.7, +1.0, +1.3, +2.0, or more). The amount needed will depend on the intensity of the backlight and how much detail you want in your subject.

- Take a Test Shot: After adjusting, take a photo and review it on your camera’s LCD screen.

- Evaluate and Refine: Check the exposure of your subject. If it’s still too dark, increase the compensation further. If it’s starting to look overexposed, reduce the compensation. Pay attention to the highlights in the background; you may need to accept some blown-out highlights for the sake of exposing your subject correctly, or you may have enough dynamic range to capture both.

The key is to find the sweet spot where your subject is well-lit without completely sacrificing the detail in the background, or vice versa, depending on your creative intent.

Metering Modes for Precise Exposure Control

Different metering modes give you varying degrees of control over how your camera measures the light in a scene. For backlit situations, selecting a metering mode that focuses on your subject is paramount.The benefits of using spot metering or center-weighted metering for precise exposure control on the subject include:

- Spot Metering: This mode measures a very small area of the scene, typically around 1-5% of the frame, often centered on the viewfinder. By placing the spot on your subject’s face or the most important part of your subject, you ensure that this specific area is correctly exposed. This is incredibly useful when your subject is small within a vast, bright background.

- Center-Weighted Metering: This mode prioritizes the center of the frame, giving more weight to readings in the middle and less to the edges. While not as precise as spot metering, it’s often a good compromise, especially if your subject is generally in the central area of your composition and you don’t want to constantly move the spot.

- Evaluative/Matrix Metering (with caution): While your camera’s default evaluative or matrix metering attempts to analyze the entire scene, it often struggles with extreme contrast ratios like those found in backlight. It might still underexpose your subject. You can often use this mode in conjunction with exposure compensation, but spot or center-weighted is generally more reliable for direct subject exposure.

Experimenting with these modes will help you understand which one best suits your shooting style and the specific backlit scenario you are facing.

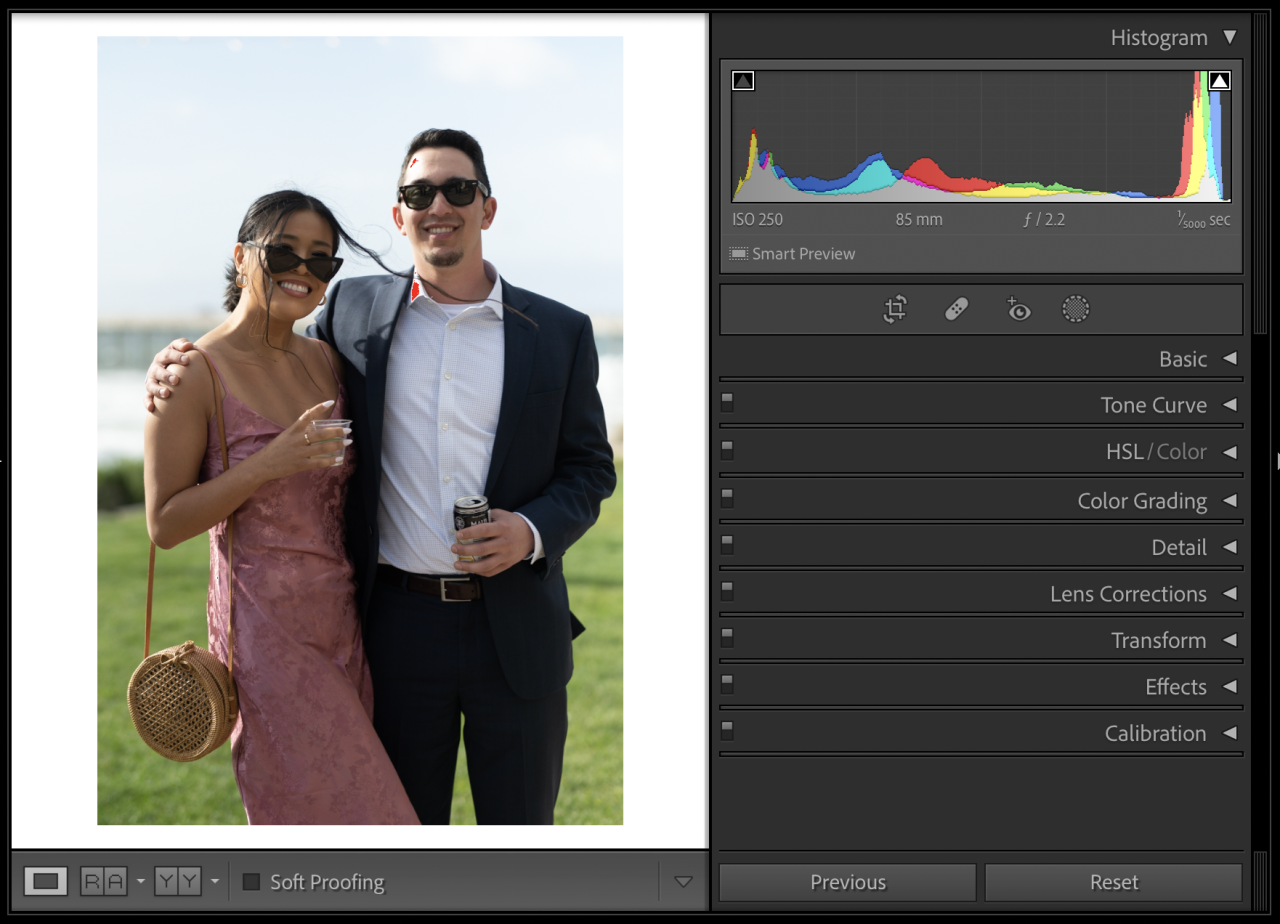

Utilizing the Histogram for Exposure Assessment

The histogram is an invaluable tool for visually assessing the exposure of your image, especially in challenging lighting. It’s a graph that shows the distribution of tonal values in your photograph, from pure black on the left to pure white on the right, with mid-tones in between.Here’s how to utilize the histogram to avoid clipping highlights or shadows:

- Display the Histogram: After taking a shot, navigate through your camera’s playback options to display the histogram for that image.

- Analyze the Graph:

- Left Side (Shadows): If the graph is heavily bunched up on the far left, it indicates that large areas of your image are pure black, meaning you’ve lost shadow detail (shadow clipping).

- Right Side (Highlights): If the graph is heavily bunched up on the far right, it indicates that large areas of your image are pure white, meaning you’ve lost highlight detail (highlight clipping).

- Middle (Mid-tones): The bulk of the graph should ideally fall within the mid-tones, indicating a good balance of light and dark areas.

- Adjust Exposure Based on Histogram:

- If you see significant clipping on the right (highlights), you may need to decrease exposure compensation or consider if the scene’s dynamic range exceeds your camera’s capabilities.

- If you see significant clipping on the left (shadows) and your subject is underexposed, you will need to increase exposure compensation.

- The goal is to have the histogram spread across the graph without being excessively bunched up on either extreme, especially if you aim to retain detail in both the shadows and highlights. However, in strong backlight, you might prioritize exposing for the subject, accepting some blown highlights.

The histogram provides an objective measure of your exposure, helping you make informed decisions about adjusting your camera settings.

Recommended Camera Settings for Backlight Scenarios

The ideal camera settings for shooting in backlight will vary depending on the specific situation, your desired outcome, and the capabilities of your camera. However, there are general guidelines that can help you achieve better results.Here is a list of recommended camera settings for different scenarios involving backlight:

Scenario 1: Silhouetting Your Subject

In this case, you want the bright background to dominate and your subject to be a dark shape.

- ISO: As low as possible (e.g., ISO 100 or 200) to minimize noise.

- Aperture: This is flexible and depends on your creative intent. A wider aperture (lower f-number like f/1.8, f/2.8) will create a shallow depth of field, blurring the background and emphasizing the silhouette. A narrower aperture (higher f-number like f/8, f/11) will keep more of the background in focus.

- Shutter Speed: Adjust to achieve correct exposure for the background. You will likely need a faster shutter speed to prevent overexposure of the bright sky or light source.

- Metering: Evaluative or Matrix metering is often suitable here, as you want the camera to expose for the bright background.

- Exposure Compensation: Typically, you’ll want to underexpose by -1 to -2 stops, or even more, to ensure your subject becomes a silhouette.

Scenario 2: Exposing Your Subject with a Bright Background

This is the most common scenario where you want your subject to be well-lit while still showing the beautiful light in the background.

- ISO: Keep as low as possible, but be prepared to increase it if necessary to maintain a usable shutter speed or aperture.

- Aperture:

- For portraits, a wider aperture (f/1.4 – f/4) will isolate your subject from the background and create a pleasing bokeh, even with backlight.

- For landscapes or scenes where you want more depth of field, a narrower aperture (f/8 – f/16) will keep more of the scene in focus.

- Shutter Speed: This will be adjusted to balance the exposure. If your aperture and ISO are set, you’ll fine-tune the shutter speed. For handheld shots, ensure it’s fast enough to avoid camera shake (e.g., 1/focal length or faster).

- Metering: Spot metering on your subject’s face or center-weighted metering is highly recommended.

- Exposure Compensation: You will almost always need positive exposure compensation (+0.7 to +2.0 stops or more) to brighten your subject. Review your histogram to ensure you’re not clipping highlights excessively.

Scenario 3: Capturing Dramatic Rim Lighting (Hair Light)

Backlight is excellent for creating a bright Artikel or “rim” around your subject, separating them from the background and adding a professional look.

- ISO: Low is preferred, but can be increased if needed.

- Aperture: A wider aperture is often used to create a shallow depth of field, further enhancing the separation and making the rim light pop.

- Shutter Speed: Adjust for the subject’s exposure.

- Metering: Spot metering on the subject’s face or center-weighted metering is crucial to get the subject correctly exposed.

- Exposure Compensation: Positive exposure compensation will be necessary to illuminate the subject’s front, but you’ll need to be mindful of how this affects the background and the strength of the rim light. Sometimes, a slightly less positive compensation might preserve a more defined rim light.

In all backlit situations, remember that the dynamic range of your camera plays a significant role. If the difference between the brightest and darkest parts of the scene is too extreme, you may need to use techniques like HDR (High Dynamic Range) photography or fill flash to achieve a balanced exposure.

Mastering Light Manipulation to Complement Backlight

Shooting directly into a strong light source can be one of the most challenging scenarios for photographers. While it often results in silhouette effects, there are numerous techniques to harness this powerful light and still achieve a well-exposed subject. This section delves into how to actively manipulate light to your advantage when faced with strong backlight, ensuring your subjects are not lost in the glare.Mastering light manipulation involves understanding how to introduce or redirect light to balance the extreme contrast.

This can be achieved through various methods, from utilizing built-in camera features to employing external lighting and reflective surfaces. The goal is to fill in the shadows on your subject without overpowering the natural beauty of the backlight.

Fill Flash for Subject Illumination

Fill flash is a crucial technique for mitigating the high contrast ratio inherent in backlight situations. By introducing a controlled burst of light from your flash, you can effectively illuminate your subject, bringing out details that would otherwise be lost in shadow. This doesn’t mean overpowering the background; rather, it’s about subtly lifting the subject’s exposure to a more balanced level.When using fill flash, it’s important to control its intensity.

Modern cameras and external flashes offer settings to adjust flash power, allowing you to fine-tune the amount of light added. For instance, using a flash exposure compensation setting can reduce the flash output by a specific number of stops, ensuring it acts as a subtle fill rather than the primary light source. Experimenting with different power levels is key to finding the sweet spot where the subject is adequately lit without appearing artificially bright.

- Flash Power Adjustment: Many cameras allow you to dial down the flash output using flash exposure compensation (FEC). A common starting point is to reduce it by -1 or -2 stops to avoid an overly “flashed” look.

- Flash Metering Modes: Utilize TTL (Through-The-Lens) metering for your flash, which allows the camera to automatically determine the correct flash output based on the scene’s lighting.

- Bounce Flash: If using an external flash, bouncing the flash off a nearby surface (like a ceiling or wall) can diffuse the light and create a softer, more natural illumination on the subject.

- Using a Diffuser: Attaching a diffuser to your flash softens the light further, reducing harsh shadows and creating a more flattering effect on the subject.

Reflector Techniques for Ambient Light Bounce

Reflectors are invaluable tools for photographers, especially in backlight. They work by capturing the available ambient light and bouncing it back onto your subject, effectively filling in shadows and reducing the contrast ratio. This method is particularly effective when the backlight is strong, as there is ample light to redirect.The type of reflector and its placement are critical. Silver reflectors offer a brighter, cooler light, while gold reflectors provide a warmer tone, which can be flattering for skin tones.

White reflectors offer a neutral fill. Positioning the reflector opposite the light source, or at an angle that catches the light and directs it towards the shadowed areas of your subject, is essential. Even a simple white piece of card or a light-colored wall can act as a makeshift reflector.

“A reflector is essentially a controllable mirror for ambient light, allowing you to sculpt the shadows and highlights on your subject.”

Subject and Camera Positioning for Backlight Control

Strategic positioning of your subject or camera can significantly alter the perceived intensity and direction of the backlight. Sometimes, the simplest solution is to adjust where your subject stands or where you place your camera relative to the light source.If the backlight is too harsh, consider moving your subject slightly to the side, so the light hits them from a 45-degree angle rather than directly from behind.

Alternatively, you can reposition yourself to use the backlight more as a rim light, creating a beautiful halo effect around your subject while still ensuring they are adequately lit from the front or side. Using foreground elements, such as trees or buildings, to partially obscure the sun can also help to diffuse its intensity.

- Subject Angle Adjustment: Rotating the subject a few degrees can change how the light wraps around them, often softening the harshness and creating more flattering contours.

- Camera Angle Adjustment: Lowering or raising your camera can change the relationship between the subject, the light source, and the background, potentially finding a more balanced exposure.

- Utilizing Foreground Elements: Placing objects in the foreground can act as natural diffusers or create pockets of shade that help control the intensity of the backlight on the subject.

- Subject-to-Background Distance: Increasing the distance between your subject and the background can help the background blow out to pure white, which can be an intentional artistic choice and simplifies the exposure challenge for the subject.

Comparative Analysis: Artificial Light vs. Natural Reflectors

Both artificial light sources (like flashes) and natural reflectors serve the purpose of filling shadows in backlight situations, but they offer distinct characteristics and require different approaches. Understanding these differences allows photographers to choose the most appropriate tool for their specific creative vision and shooting conditions.Artificial light, such as a speedlight or studio strobe, offers precise control over the intensity, color temperature, and direction of the light.

It can be used to precisely illuminate specific areas of the subject or to overpower the backlight entirely if necessary. However, artificial light can sometimes appear unnatural if not used subtly, and it requires power sources and potentially more equipment. Natural reflectors, on the other hand, are often more readily available and produce softer, more natural-looking light. They rely on the existing ambient light, making them a passive but effective solution.

The downside is that their effectiveness is entirely dependent on the available light, and they offer less precise control over the quality and direction of the fill light.

| Feature | Artificial Light (e.g., Flash) | Natural Reflectors (e.g., White Card, Wall) |

|---|---|---|

| Control over Light | High: Precise control over intensity, direction, and color temperature. | Moderate: Dependent on ambient light direction and intensity; less precise. |

| Light Quality | Can be harsh if direct; can be softened with modifiers. | Generally soft and natural, mimicking ambient light. |

| Portability and Setup | Requires power source, modifiers, and potentially stands; can be more complex. | Highly portable, easy to set up, often readily available. |

| Cost | Can be a significant investment for quality equipment. | Minimal to none, especially with improvised solutions. |

| Effectiveness in Low Light | Can create light where none exists. | Limited by the amount of available ambient light to bounce. |

Lens Selection and Creative Use of Backlight

The choice of lens significantly influences how backlight is rendered in your photographs, offering a range of creative possibilities. Understanding these nuances will empower you to harness backlight more effectively, whether you aim to embrace its dramatic effects or mitigate its challenges. Different focal lengths and lens constructions interact with light sources in distinct ways, shaping the final image’s mood and aesthetic.The interplay between your lens, aperture, and a strong backlight is a fundamental aspect of photographic artistry.

By carefully considering these elements, you can transform what might seem like a difficult lighting situation into a powerful tool for visual storytelling. This section explores how lens selection, aperture control, and intentional light manipulation can lead to stunning results when shooting against the light.

Impact of Lens Types on Backlight Rendering

Different focal lengths and lens designs offer unique perspectives and interactions with backlight. Wide-angle lenses can capture expansive scenes, often including the light source prominently, while telephoto lenses compress the scene and can isolate subjects against a bright background. Prime lenses, known for their simpler construction, may exhibit different flare characteristics compared to zoom lenses.

- Wide-Angle Lenses: These lenses, with their broad field of view, are excellent for including the entire scene, often incorporating the sun or other strong light sources directly into the frame. This can lead to dramatic sunbursts or expansive skies. The wider perspective means more of the light source is visible, increasing the likelihood of lens flare but also allowing for grand compositions.

- Telephoto Lenses: Telephoto lenses, with their narrower field of view, are adept at isolating subjects and compressing the background. When shooting into backlight with a telephoto lens, the subject can become a distinct silhouette against a brightly lit background, creating a strong sense of separation and drama. They can also produce a more focused and intense rendition of the light source itself, often with more pronounced bokeh.

- Prime Lenses: Prime lenses, lacking zoom mechanisms, often have simpler optical formulas. This can sometimes result in more predictable and aesthetically pleasing lens flare patterns compared to complex zoom lenses. Many photographers prefer prime lenses for their sharpness and often wider maximum apertures, which are beneficial in controlling depth of field and light.

Aperture’s Influence on Lens Flare and Bokeh

The aperture setting is a critical control for managing the appearance of lens flare and the quality of bokeh when shooting into backlight. A wider aperture (smaller f-number) generally leads to softer, more diffused bokeh and can influence the shape and intensity of lens flare. A narrower aperture (larger f-number) can create sharper, more defined starburst effects from light sources.

- Wide Apertures (e.g., f/1.8, f/2.8): Using a wide aperture will result in a shallow depth of field, beautifully blurring the background and any light sources. This can create soft, pleasing circles of light (bokeh balls) from distant lights. Lens flare at wide apertures tends to be more diffuse and less defined, often appearing as a soft glow or haze, which can add a dreamy quality to the image.

- Narrow Apertures (e.g., f/11, f/16): Stopping down the aperture to a narrower setting will increase the depth of field, bringing more of the scene into focus. Crucially, it will transform point light sources into distinct starbursts or sunstars. The number of points on the starburst typically corresponds to the number of aperture blades in the lens; an even number of blades usually results in twice that number of points.

This effect is highly sought after for its dramatic visual impact.

Intentional Creation and Avoidance of Lens Flare

Lens flare, often perceived as a technical flaw, can be a powerful creative element when used intentionally. Conversely, understanding how to avoid it is essential when it detracts from the image.

- Creating Lens Flare: To intentionally create lens flare, position the light source so it enters the front of your lens at an angle. Experiment with different angles and aperture settings. A wider aperture might produce a more ethereal glow, while a narrower aperture will yield distinct starburst patterns. Sometimes, a slight nudge of the camera or subject can introduce or alter the flare’s appearance.

Prime lenses with fewer internal elements are often more prone to producing pleasing, artistic flare.

- Avoiding Lens Flare: To minimize unwanted lens flare, use a lens hood. A lens hood physically blocks stray light from hitting the front element of your lens. If a lens hood is not sufficient or available, try repositioning your camera slightly to change the angle of the light source relative to the lens. Shooting at an angle where the light source is not directly in front of the lens can also help.

Sometimes, adjusting your position or the subject’s position can solve the problem.

Scenarios for Creating Dramatic Silhouettes with Backlight

Silhouettes are a classic and impactful use of strong backlight, where the subject is rendered as a dark shape against a brightly illuminated background. This technique emphasizes form, Artikel, and mood, stripping away detail to focus on the essential shape.

- The Lone Figure Against a Sunset: Imagine a person standing on a beach or a hilltop as the sun sets. By exposing for the bright sky, the person will become a dark, graphic shape. The key is to place the subject between the camera and the light source. This works exceptionally well with distinct profiles, such as a person looking out at the horizon or a dancer in motion.

- Architectural Artikels: Buildings or iconic structures can create stunning silhouettes against a vibrant sky, especially during golden hour or twilight. The backlight will highlight the architectural details as an Artikel, turning a familiar building into a dramatic graphic element. Consider shooting from a low angle to emphasize the sky and the building’s form.

- Natural Forms: Trees, branches, or even mountain ranges can be transformed into dramatic silhouettes. The intricate patterns of branches against a bright sky can be particularly captivating. Look for strong, recognizable shapes that are enhanced by being rendered in shadow.

- Action Shots: Athletes in mid-action, like a surfer riding a wave or a cyclist leaping, can create dynamic and energetic silhouettes. The backlight freezes their movement in a stark, graphic form, emphasizing the athleticism and the power of the moment. The surrounding light can often add color and drama to the background.

Post-Processing Strategies for Backlit Images

Shooting against strong backlight can create dramatic and artistic images, but it often presents challenges that require careful attention during post-processing. The goal is to harness the existing light and correct any imbalances to reveal the full potential of your photograph. This section will guide you through the essential editing techniques to transform your backlit shots into polished masterpieces.The inherent contrast in backlit images, with bright highlights and deep shadows, can be managed effectively with precise adjustments in editing software.

Understanding how to manipulate exposure, contrast, and local adjustments is key to bringing out detail without sacrificing the mood or artistic intent of the original shot.

Adjusting Exposure and Contrast to Recover Detail

Recovering detail in both the bright, blown-out areas and the dark, shadowy regions of a backlit image is a fundamental step in post-processing. Editing software provides powerful tools to achieve this balance, allowing you to reveal textures and information that might initially appear lost.The primary tools for this task are the exposure, highlights, shadows, whites, and blacks sliders. When working with backlit images, it’s common to need to decrease the exposure slightly to protect the bright background, and then use the shadows slider to lift the darker areas of the subject.

Conversely, if the subject is well-exposed but the background is too bright, you might use the highlights slider to bring down those areas.

- Exposure: This global slider affects the overall brightness of the image. Use it cautiously, as over-adjustment can lead to noise or a washed-out appearance.

- Highlights: Specifically targets the brightest areas of the image. Lowering this slider can recover detail in the sky or bright reflections.

- Shadows: Targets the darkest areas. Increasing this slider can reveal detail in the subject’s face or clothing that was in shadow.

- Whites: Affects the clipping point of the white areas. Adjusting this can help define the brightest points in the image without blowing them out completely.

- Blacks: Affects the clipping point of the black areas. Lowering this can deepen the shadows for more contrast, but be careful not to crush them entirely, losing all detail.

A common workflow involves first adjusting the exposure to a point where the brightest areas are manageable, then using the shadows slider to bring up the detail on your subject. Subsequently, fine-tune the highlights and blacks to achieve the desired contrast and tonal range. Remember to zoom in to 100% to check for noise or banding, especially when significantly lifting shadows.

Selective Dodging and Burning for Light Balance

Dodging and burning are traditional darkroom techniques that are expertly replicated in digital editing software. These tools allow for precise, localized adjustments to exposure, enabling you to selectively lighten (dodge) or darken (burn) specific areas of your image. This is particularly effective in backlit situations for balancing the light between the subject and the background, or for drawing attention to key elements.When working with a backlit image, you might dodge the subject’s face to bring it forward and make it more prominent, or burn the edges of the background to emphasize the silhouette effect.

The key is to make these adjustments subtly and gradually, mimicking natural light fall-off.

- Dodging: Use the dodge tool to selectively lighten areas. This is ideal for bringing out detail in the shadows of your subject or subtly brightening eyes.

- Burning: Use the burn tool to selectively darken areas. This is useful for reducing the brightness of the background or adding depth to darker parts of the scene.

When applying these tools, it’s crucial to use a soft brush with a low opacity and flow. This ensures that the adjustments blend seamlessly with the surrounding pixels. Work in small increments, building up the effect gradually until you achieve the desired balance. Pay close attention to the edges of your dodged or burned areas to avoid creating unnatural halos or abrupt transitions.

Enhancing Rim Lighting Through Color Grading and Sharpening

Backlight often creates a beautiful rim light, or halo, around the subject. Post-processing can be used to enhance this effect, making it more pronounced and visually striking. Color grading and sharpening are two powerful techniques that can elevate the quality of this rim lighting.Color grading involves adjusting the color balance of specific areas. For rim lighting, you might introduce a subtle complementary color to the rim light to make it pop.

For instance, if the backlight is a warm golden hour light, you could introduce a touch of blue or purple into the shadows to create a pleasing contrast. Sharpening can be applied selectively to the edges where the rim light is most prominent, making the Artikel of the subject crisper and more defined.

- Color Grading: Use color balance, hue/saturation, or split toning tools to add subtle color shifts to the rim light. For example, a warm backlight might benefit from a slight cool tone in the surrounding areas to create separation.

- Selective Sharpening: Apply sharpening specifically to the edges of the subject that are catching the backlight. This will make the silhouette effect more defined and emphasize the separation from the background.

When applying sharpening, it’s important to use masking to ensure that the sharpening is only applied to the desired areas. Over-sharpening can introduce artifacts and an unnatural look, so always apply it judiciously and at a moderate level.

Workflow for Retouching Backlit Portraits

Retouching backlit portraits requires a systematic approach to ensure that the skin tones are natural and the subject is well-separated from the background, while still respecting the dramatic lighting. The goal is to enhance the existing beauty of the image without making it look over-edited.A typical workflow would begin with basic global adjustments, followed by localized enhancements, and finally, attention to finer details.

The dramatic contrast inherent in backlit portraits can be a double-edged sword; it can create mood but also obscure features if not handled correctly.

- Initial Global Adjustments: Start by adjusting exposure, highlights, and shadows to bring out the essential detail in the subject’s face and body. Ensure the eyes are visible and the overall brightness is pleasing.

- Subject Separation: Use dodging and burning to gently lift the subject’s features and darken the background if necessary. This helps the subject stand out.

- Skin Tone Correction: Backlight can sometimes cast unnatural color casts on the skin. Use white balance adjustments and selective color correction tools to ensure the skin tones appear natural and healthy. Pay attention to the warmth or coolness introduced by the backlight and correct accordingly.

- Enhancing Eye Detail: Eyes are often a focal point. Dodge the pupils and irises slightly and add a tiny specular highlight to make them sparkle.

- Refining the Rim Light: If a desirable rim light is present, consider subtly enhancing its color and brightness using selective color grading and dodging.

- Final Touches: Apply a gentle overall sharpening and noise reduction if needed. Ensure that the final image has a good tonal range and the subject is clearly defined.

“In backlit portraits, the aim is to sculpt with light in post-processing, revealing form and detail without erasing the drama of the original lighting.”

Remember to work non-destructively by using adjustment layers and smart objects, allowing you to revisit and refine your edits at any stage. This approach ensures flexibility and preserves the quality of your original image throughout the retouching process.

Practical Scenarios and Solutions for Backlight Photography

Navigating the complexities of backlight photography often involves anticipating common challenges and implementing targeted solutions. This section delves into specific situations where backlight can be particularly tricky, offering practical advice and proven techniques to overcome them, ensuring your images are both technically sound and creatively compelling.

Backlight Photography Challenges and Solutions Table

Understanding the specific problems that arise from shooting into a strong light source is the first step towards effective management. The following table Artikels common challenges encountered during backlight photography and provides actionable solutions to address them.

| Challenge | Solution |

|---|---|

| Subject Underexposed (Silhouetted) | Use fill flash or a reflector to add light to the subject. Increase exposure compensation or manually adjust exposure to prioritize the subject. |

| Harsh Lens Flare Obscuring the Subject | Use a lens hood to block stray light. Adjust your shooting angle slightly to minimize direct light entering the lens. |

| Loss of Detail in Shadows | Shoot in RAW format to retain more data for post-processing. Use techniques like exposure bracketing for HDR processing. |

| Difficulty Achieving Sharp Focus | Utilize your camera’s focus assist beam or manual focus. Select a single focus point and aim it at a high-contrast area of the subject. |

| Washed-Out Backgrounds | Expose for the background and use fill flash or reflectors for the subject. Consider shooting at a time when the backlight is less intense. |

Outdoor Portraits During Golden Hour with a Bright Sky

Golden hour, the period shortly after sunrise or before sunset, offers beautiful warm light. However, a bright sky during this time can still create a significant backlight scenario, potentially underexposing your subject. The key is to balance the exposure between the sky and your subject.One effective strategy is to use a combination of exposure settings and light modification. Aim to expose for the sky to retain its color and detail.

Then, use a reflector placed strategically to bounce light back onto your subject’s face, filling in the shadows. Alternatively, a subtle use of fill flash can achieve a similar effect, ensuring your subject is well-lit without looking artificial. For portraits, a wider aperture can help isolate your subject from the bright background, creating a pleasing bokeh.

Photographing Subjects in Front of Windows with Strong Natural Light

Shooting with a window as the primary light source, especially when it’s bright outside, presents a classic backlight situation. The window acts as a powerful backlight, often making the subject appear as a silhouette.To overcome this, you can approach the subject from an angle that allows some of the window light to fall on their face, acting as a natural rim light.

If the window is the sole light source and the subject is too dark, consider moving the subject closer to the window but slightly to the side, so the light wraps around them. If possible, position yourself so that the window is to the side of your subject, rather than directly behind them. When the window is directly behind the subject, using a large diffuser placed between the window and the subject can soften the light and reduce the contrast, making the subject more visible.

In cases where the window light is extremely strong, exposing for the window might be necessary, and then using a carefully controlled fill flash or a reflector can bring the subject’s details back into view.

Shooting Moving Subjects Against a Bright Background

Capturing action with a bright background, such as a runner on a beach with the sun behind them, requires quick thinking and precise camera control. The challenge is to freeze the motion of the subject while properly exposing them against the bright backdrop.Here is a step-by-step procedure:

- Pre-focus: Before the subject enters the frame, pre-focus on a point where you anticipate they will be. This is crucial for action shots.

- Set Shutter Speed: Choose a fast shutter speed (e.g., 1/500 sec or faster) to freeze the motion of the subject. This is your priority for action photography.

- Adjust Aperture: Based on your desired depth of field and the available light, adjust your aperture. A slightly smaller aperture (higher f-number) can help ensure more of the moving subject is in focus.

- Manage Exposure: If your camera has a dedicated backlight compensation setting, use it. Otherwise, you will likely need to increase your exposure compensation significantly (e.g., +1 to +2 stops) or manually set your exposure to prioritize the subject’s brightness, accepting that the background might be slightly overexposed.

- Use Continuous Shooting Mode: Fire off a burst of shots as the subject moves through your pre-focused area. This increases your chances of capturing the perfect moment.

- Consider Fill Flash (if applicable): For added detail on the subject, a powerful, fast-recycling flash unit set to a low power can be used to provide a subtle fill. Ensure it’s synchronized correctly with your shutter speed.

Final Summary

By mastering these techniques, you’ll gain the confidence to conquer backlit scenes, transforming them from a photographer’s nightmare into a canvas for breathtaking imagery. From clever camera adjustments and light manipulation to thoughtful lens choices and post-processing finesse, this comprehensive approach ensures your subjects shine, even when the sun is directly behind them.